Inside ITER’s Tokamak Assembly Preparation Building in southern France, a four-metre-tall industrial robot known informally as “Godzilla” is being used to test the installation of thousands of components that will eventually line the interior of the reactor’s vacuum vessel. The machine can lift more than two metric tons and is helping engineers refine the procedures required to assemble the internal systems of the world’s largest fusion experiment. ITER is expected to reach full magnetic energy in the next decade, followed by deuterium-tritium fusion operations. These preparations reflect the scale and precision required to construct a tokamak, a device designed to confine plasma at temperatures exceeding those found in the core of the sun.

A tokamak confines plasma using magnetic fields rather than physical containment. Its toroidal structure houses superconducting magnets that generate a powerful magnetic field around the vacuum chamber. A secondary magnetic field, produced by currents within the plasma itself, combines with the primary field to create a helical confinement structure. Charged particles spiral along these magnetic field lines, allowing the plasma to remain suspended without contacting the reactor walls. This arrangement is necessary because fusion reactions require temperatures above 100 million degrees Celsius, far beyond the tolerance of any solid material.

Fusion occurs when isotopes of hydrogen, typically deuterium and tritium, collide with sufficient energy to overcome electrostatic repulsion. The reaction produces helium nuclei and high-energy neutrons. These neutrons escape magnetic confinement and deposit their energy into surrounding materials, producing heat that can be converted into electricity. Maintaining stable plasma requires precise control of temperature, density, and magnetic configuration. Plasma is inherently unstable, and small disturbances can trigger disruptions that terminate confinement.

Recent experimental work has demonstrated progress in overcoming key operational limits. China’s Experimental Advanced Superconducting Tokamak has achieved plasma densities exceeding previously established limits by improving control over plasma boundary conditions and reducing impurity accumulation. These experiments confirmed theoretical predictions regarding the role of plasma-wall interactions in triggering instability and demonstrated that improved boundary control can sustain higher density plasma. Higher plasma density increases fusion reaction rates and improves the efficiency of confinement systems.

The construction and operation of tokamaks require integration of advanced superconducting magnet systems, structural engineering, and robotic assembly. ITER’s vacuum vessel contains thousands of components, including superconducting magnet coils, neutron shielding blanket modules, cooling channels, and diagnostic systems. These components must function under combined thermal, electromagnetic, and radiation loads. Assembly procedures rely on robotic manipulators capable of positioning large components with high precision. These robotic systems operate in confined and restricted environments, where direct human access is limited.

Superconducting magnets are central to tokamak performance. Higher magnetic field strength improves plasma confinement and allows more efficient reactor designs. High-temperature superconductors allow magnets to carry extremely large electrical currents while operating at cryogenic temperatures. Improvements in superconducting materials enable stronger magnetic fields and more compact confinement systems. This superconducting magnet development has relevance for applications requiring compact and efficient high-power electromagnetic systems.

Materials used inside tokamaks must withstand sustained neutron exposure and intense thermal stress. Neutron bombardment alters the atomic structure of materials over time, affecting their strength and durability. Plasma-facing components must tolerate high heat flux while maintaining structural stability and limiting impurity release. Research in this area has produced improved radiation-resistant alloys, ceramics, and composite materials capable of operating in extreme environments.

Tokamak research also advances robotic and remote handling systems designed for operation in hazardous environments. Robotic manipulators developed for fusion reactor assembly and maintenance perform installation, inspection, and replacement tasks in areas where radiation or physical constraints prevent human access. These systems include precision positioning mechanisms and automated tool exchange capability. Their development improves the reliability of maintenance operations in physically restricted environments.

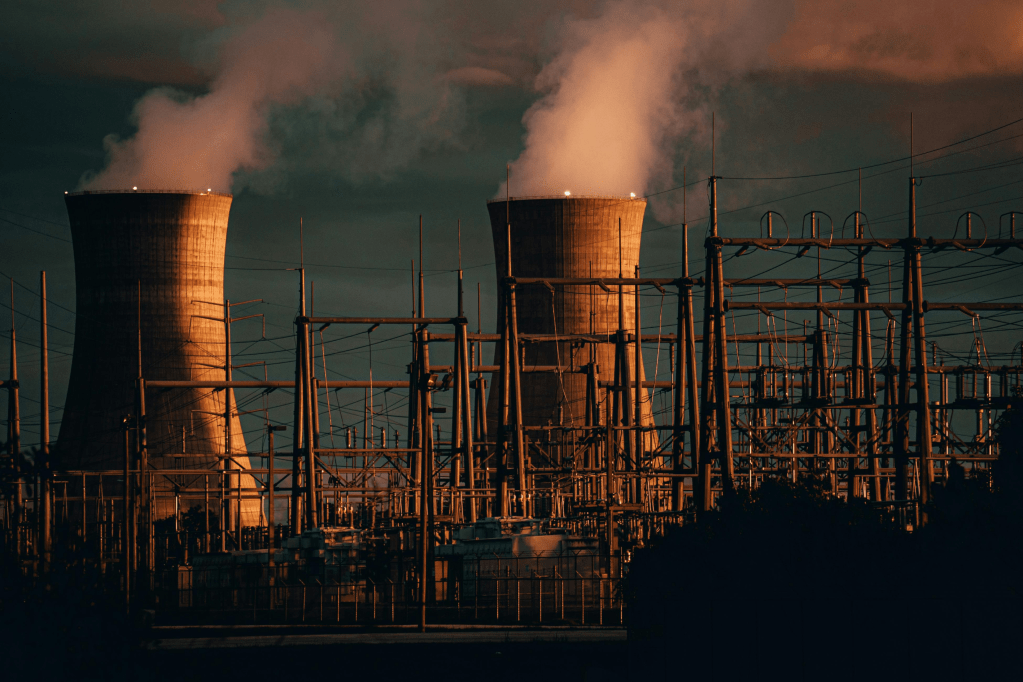

The energy implications of tokamak development are particularly relevant to defense infrastructure. Military operations require continuous and reliable electrical power at fixed installations, naval bases, and remote facilities. Fusion reactors, once operational, could provide sustained power generation using fuel derived from widely available sources. Deuterium can be extracted from seawater, and tritium can be produced within the reactor using lithium. This allows energy production independent of conventional fuel supply chains.

Naval platforms require sustained onboard electrical generation for propulsion, sensors, and onboard systems. Fusion energy systems could provide continuous electrical output without frequent refuelling. This would allow extended operational endurance and reduce dependence on fuel logistics.

Tokamak development also contributes to improvements in thermal management and high-capacity electrical systems. Fusion reactors must remove sustained heat loads while maintaining stable operation. Cooling systems and power handling infrastructure developed for tokamaks improve the ability to operate high-energy systems reliably over long periods.

International fusion programs continue to advance tokamak performance and reactor engineering. ITER represents the largest coordinated fusion project, involving global industrial participation. Experimental tokamaks in multiple countries continue to refine plasma confinement, superconducting magnet design, and structural performance. These efforts contribute to improvements in superconductors, structural materials, robotics, and high-power electrical systems.

The use of heavy robotic systems during ITER assembly and the recent advances in plasma density control demonstrate steady progress in fusion reactor engineering. While operational fusion power plants remain under development, the engineering progress associated with tokamaks is already contributing to improvements in superconducting systems, radiation-resistant materials, robotic maintenance capability, and high-power electrical infrastructure. These developments have direct relevance to military systems that depend on reliable energy, durable materials, and sustained operation in demanding environments.

(Image: Hefei Institutes of Physical Science)

Leave a comment