For much of the past three decades, defense innovation has been dominated by platforms. Fighter aircraft, missile interceptors, precision munitions and unmanned systems have captured most of the attention and investment. Radar technology, while essential, remained largely in the background, treated as a mature capability rather than a strategic differentiator. That assumption no longer holds.

The June 2025 war between Israel and Iran marked a turning point. While much of the public focus centered on air strikes, missile launches, and intercepts, defense planners and analysts drew a different conclusion. The conflict demonstrated that the decisive factor in modern air and missile warfare is not the interceptor itself, but the sensor network that detects, tracks, classifies, and manages threats across time and space. Radar has moved from a supporting role to the center of modern defense architecture.

During the conflict, Israel faced a layered threat environment that included ballistic missiles, cruise missiles, long range strike drones, and coordinated salvos designed to stress defensive systems. Successfully managing this environment depended on continuous detection and tracking at long range, rapid handoff between sensors, and the ability to maintain a coherent air picture under heavy electronic warfare conditions. Radar performance determined whether defenses could respond in time and whether command systems could prioritize the most dangerous threats.

This reality is driving a global reassessment of radar technology. Armed forces are no longer looking for single purpose sensors tied to specific weapons. They are investing in flexible, multi mission radar systems capable of supporting integrated air and missile defense, maritime surveillance, counter drone operations, and early warning simultaneously. The goal is persistent situational awareness rather than isolated detection.

Advances in active electronically scanned array technology have enabled this shift. Modern AESA radars can change beam direction, waveform, and mission focus almost instantaneously through software rather than mechanical movement. This allows a single radar to search, track, and provide fire control data at the same time. The widespread adoption of gallium nitride semiconductors has further increased power efficiency and detection range while reducing system size and cooling requirements.

Israel Aerospace Industries’ Elta Group illustrates this transition. Its Multi Mission Radar family, now deployed globally, was designed from the outset to operate as part of a network rather than as a standalone sensor. The latest evolution integrates radar data with electro optical sensors and signal intelligence inputs, producing a unified picture that supports both human decision makers and automated defense systems. This type of sensor fusion is increasingly seen as essential in high density threat environments.

Europe is following a similar path. Italy’s Michelangelo Dome program places advanced radar at the core of a national integrated air and missile defense system. Leonardo’s next generation long range radars are designed to detect and track ballistic missiles at distances measured in thousands of kilometers, while simultaneously supporting engagement coordination and early warning for allied forces. These systems reflect a broader European effort to build sensor driven defense architectures that can operate independently or as part of NATO networks.

The United States has also elevated radar to a strategic priority. Programs such as the Lower Tier Air and Missile Defense Sensor and long range discrimination radars are intended to close gaps in coverage and provide continuous 360 degree awareness. These systems are increasingly mobile, deployable, and interoperable, reflecting lessons learned from conflicts where static infrastructure proved vulnerable.

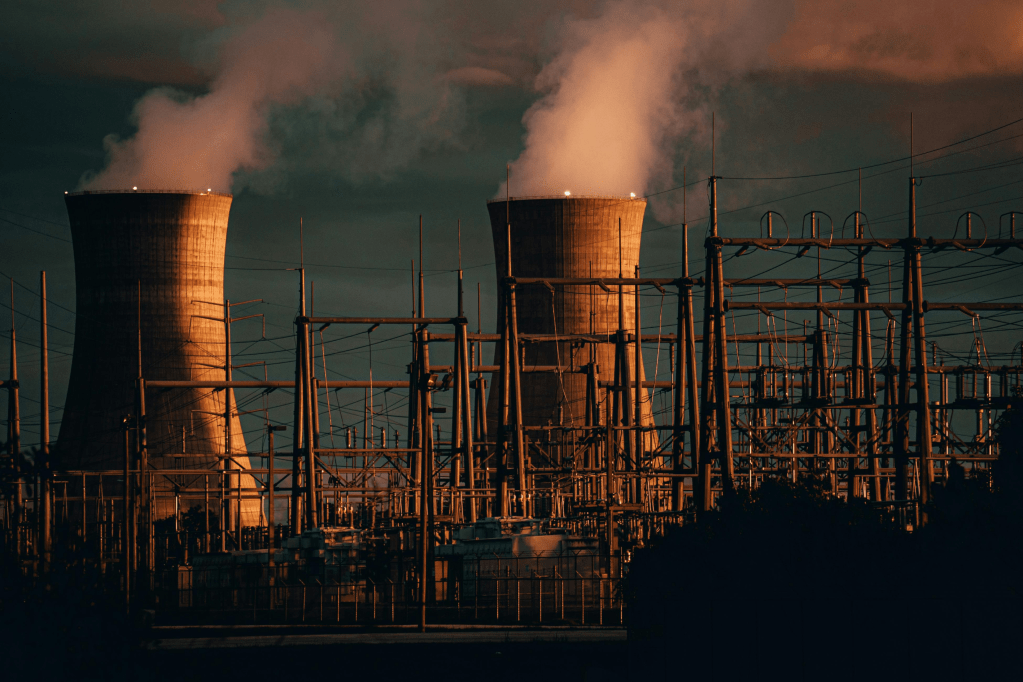

Radar investment is not limited to land based systems. Sea based radars, including some of the largest and most powerful sensors ever built, are being used to extend detection range beyond national borders and provide early warning against long range missile launches. These platforms feed data directly into joint and allied command networks, reinforcing the idea that radar is now a shared strategic asset rather than a local capability.

Underlying all of these developments is a growing reliance on software and artificial intelligence. Modern radar systems generate enormous volumes of data that cannot be managed manually. Machine learning algorithms are increasingly used to filter noise, distinguish real threats from decoys, and adapt to jamming and deception in real time. This shift has transformed radar from a fixed sensor into a dynamic system that evolves during operations.

The implications extend beyond technology. Defense procurement strategies are changing as governments recognize that sensor performance defines the effectiveness of every downstream capability. Interceptors, aircraft, and command systems can only act on the information they receive. As threats become faster and more complex, the margin for error shrinks, placing unprecedented importance on early detection and accurate tracking.

With tensions between Israel and Iran again rising and the risk of renewed direct confrontation increasing, the lessons of June 2025 remain immediate rather than theoretical. The conflict showed that success in modern air and missile warfare depends on persistent detection, resilient tracking, and the ability to integrate sensors across domains under pressure. Radar systems provide the time, clarity, and decision advantage that determine whether defenses hold or fail. As both regional and global powers prepare for the possibility of escalation, radar has become one of the most consequential technologies shaping deterrence, defense readiness, and the outcome of future conflicts.

Leave a comment