Earlier this month, the Department of the Army announced the launch of the Janus Program, a next-generation nuclear power initiative designed to provide resilient and uninterrupted energy to remote bases. Developed jointly with the Department of Energy, Janus represents a return to military nuclear power after decades of dormancy. Eighty years after the Manhattan Project began in the deserts of New Mexico, the United States is once again pairing national defense with nuclear innovation.

The Janus reactors will be compact, factory-built microreactors capable of producing up to twenty megawatts of continuous electrical power for years at a time without refueling. They will be small enough to transport by standard military logistics and rapidly install on-site. Each reactor module is sealed, self-contained, and designed for passive safety, meaning that its cooling and shutdown mechanisms rely on natural physical processes such as convection and gravity rather than pumps or external power. This allows the system to safely maintain or halt operation even if communications or control links are lost.

Microreactors like Janus are distinct from traditional nuclear plants. They use high-assay low-enriched uranium (HALEU) fuel enriched to just under 20% U-235, which provides higher power density while remaining within civilian regulatory limits. The core is encased in advanced alloys that tolerate extreme heat without degrading, while the surrounding containment structure is hardened for transport and security. Some Janus concepts use high-temperature gas-cooled designs, while others rely on compact liquid-metal or molten-salt systems. The shared objective is modularity, safety, and ease of deployment under combat or expeditionary conditions.

The reactors are being designed to power entire forward operating bases, radar installations, or autonomous command networks. A single unit could sustain multiple megawatts of energy for years without fuel convoys or resupply missions. In operational terms, that translates into unprecedented energy independence. Directed-energy weapons, radar arrays, electronic-warfare systems, AI compute clusters, and logistics hubs can all operate continuously, independent of the civilian grid or vulnerable fuel chains.

The Janus Program was first announced in mid-2024, but its strategic direction solidified after the signing of Executive Order 14299, “Deploying Advanced Nuclear Reactor Technologies for National Security,” on May 23, 2025. The order directs the Department of Defense to operate a nuclear reactor at a domestic military installation by the end of fiscal year 2028. The military’s Defense Innovation Unit subsequently selected eight companies through its Advanced Nuclear Power for Installations program. Among the chosen developers are Oklo and Radiant Industries, both of which are also advancing projects under the Department of Energy’s Nuclear Reactor Pilot Program.

Secretary of the Army Dan Driscoll described the initiative as part of a broader effort to cut through bureaucratic obstacles. “We are shredding red tape and incubating next-generation capabilities in a variety of critical sectors, including nuclear power,” he said during the Association of the United States Army conference in Washington. U.S. Secretary of Energy Chris Wright emphasized the enduring partnership between the military and the DOE, noting that since the Manhattan Project, the collaboration between military planners and civilian scientists has been a defining force in American innovation.

Dr. Jeff Waksman, principal deputy assistant secretary of the Army for Installations, Energy, and Environment, who is overseeing the Janus Program, said that it will draw directly from lessons learned during Project Pele, the Department of Defense’s earlier effort to create a transportable Generation IV nuclear reactor. “The Janus Program is going to deliver real hardware, not PowerPoint slides,” he said. “By combining military oversight with DOE technical experience, we’re ready to move forward at lightning speed to make next-generation nuclear power a reality.”

Unlike the large, centralized reactors of the Cold War, Janus systems will be commercially owned and operated, with the military acting as the technical regulator and customer. The service will oversee milestone-based payments that help private firms build economically viable production models, similar to how NASA supported commercial space launch services under its COTS program. The military and DOE will also coordinate across the uranium fuel cycle, from enrichment to waste management, ensuring that the program strengthens both defense readiness and the domestic nuclear supply chain.

Parallel developments are taking place in other branches. The Department of the Air Force selected Eielson Air Force Base in Alaska for its own microreactor pilot, awarding a contract to Oklo earlier this year. The site was chosen for its isolation and energy challenges, relying heavily on coal shipments to produce electricity in winter. A single microreactor there could generate between one and fifty megawatts of power, replacing the need for continuous fuel deliveries and demonstrating long-term resilience in Arctic conditions.

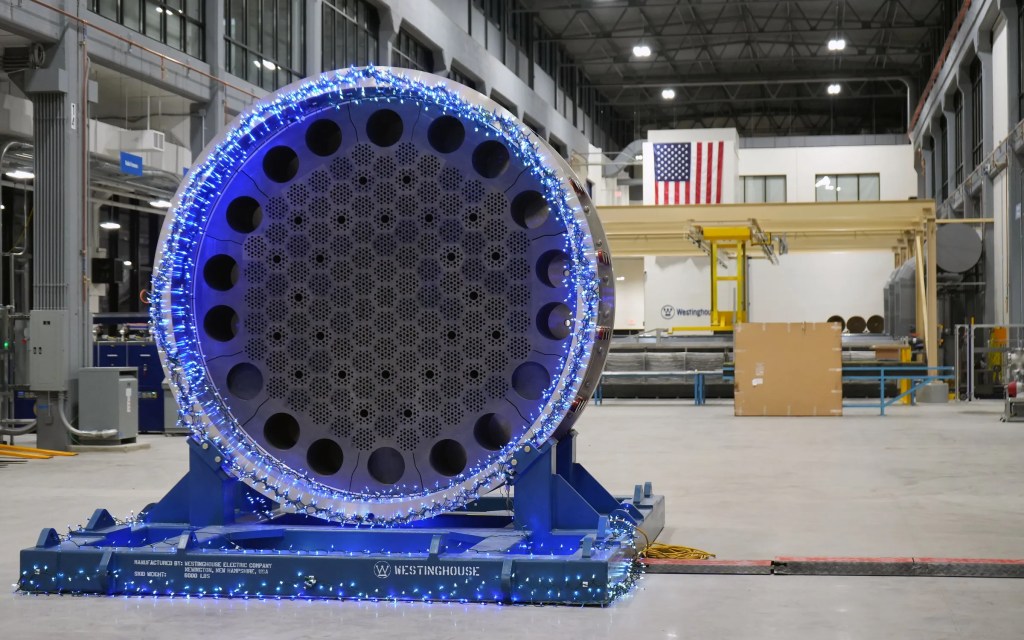

Across the private sector, several U.S. startups are developing microreactor technologies that could complement or directly supply the military’s needs. At Texas A&M University’s RELLIS campus, Last Energy is preparing to test its PWR-5 microreactor, a five-megawatt pilot derived from its modular PWR-20 system. NANO Nuclear Energy recently completed its acquisition of Global First Power in Canada, giving it a pathway to license and deploy its KRONOS micro-modular reactor in both the United States and Canada. Space Nuclear Power Corporation, or SpaceNukes, is developing a ten-kilowatt reactor for orbital testing, part of a wider effort to demonstrate nuclear systems capable of operating in remote or hostile environments.

Despite the differences in application, the technology across these programs is converging. Developers are standardizing around modular reactors that can be factory-built, shipped, and installed with minimal site preparation. Each incorporates layers of passive and active safety, redundant containment, and automated power regulation. This industrial alignment allows the military to benefit from commercial innovation without carrying the entire research burden itself. It also ensures that future defense deployments can rely on a civilian supply base capable of mass production, fuel fabrication, and maintenance.

If the Janus Program succeeds, the military could field bases that are effectively self-sustaining, able to operate for years without fuel convoys or grid dependence. That independence would redefine what it means to sustain forward operations in the twenty-first century. Nuclear energy, once a symbol of destructive power, is being reimagined as a stabilizing force for secure, long-duration military operations.

While investors and analysts focus on regulatory milestones and stock valuations, the Pentagon’s perspective is more direct. Energy has always been a limiting factor in warfare. Through Janus, the United States is betting that in the conflicts of the future, victory may depend on who can generate power the longest.

Leave a comment