When Anduril Industries and Palantir Technologies won a $100 million U.S. Army contract to prototype the Next-Generation Command and Control (NGC2) network, the partnership symbolized a new era of defense innovation. It was the embodiment of Silicon Valley’s promise to the Pentagon: move fast, cut costs, and deliver smarter, connected systems that outpace traditional defense giants.

But last week, that promise met a familiar reality.

A leaked internal Army memo described the NGC2 platform as “rife with fundamental security problems” and deemed it a “very high risk.” The document warned that the system, which links soldiers, sensors, and commanders on the battlefield, lacked essential controls – from user access verification to visibility into software security. “We cannot control who sees what, we cannot see what users are doing, and we cannot verify that the software itself is secure,” the memo stated.

Palantir and Anduril quickly pushed back, calling the report outdated and insisting that the identified vulnerabilities had already been addressed. Still, the episode underscores a growing tension within the modern defense industry: how to reconcile Silicon Valley’s “move fast and break things” ethos with the unforgiving standards of military readiness.

For decades, the Department of Defense has struggled to modernize its digital infrastructure. The emergence of private-sector disruptors, companies like Anduril, Palantir, and SpaceX, was hailed as a long-awaited breakthrough. These firms promised to deliver advanced systems in months, not years, and to infuse the defense world with the agility of the tech sector. That approach has produced undeniable successes: rapid prototyping, AI-driven analytics, and autonomous platforms that once existed only on whiteboards. Yet, as the NGC2 controversy reveals, the speed that powers innovation can also expose dangerous cracks in security and testing.

In the commercial world, a software bug might cost data or dollars. In combat, it can cost lives. A battlefield network that lacks basic access control or audit visibility isn’t merely inefficient, it’s a tactical liability. A single breach could expose troop locations, disrupt communications, or hand adversaries a digital window into military operations.

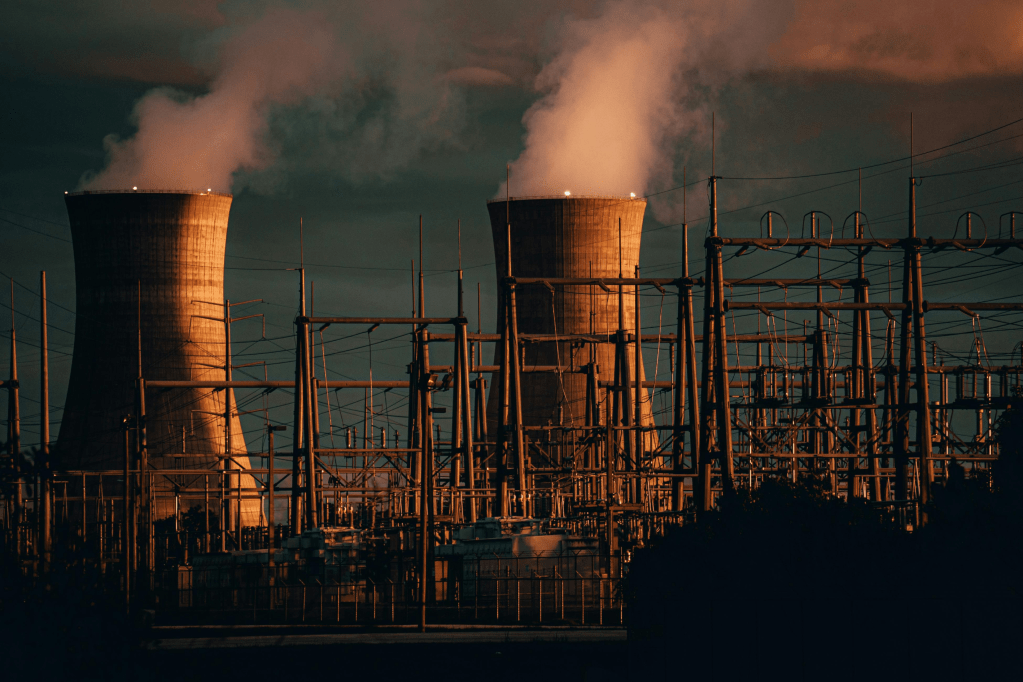

The phrase “military-grade” has become a marketing cliché. But in practice, it means something very specific: systems that can withstand not only the physical rigors of war (heat, dust, shock) but also the cyber and operational stresses of contested environments. Every piece of software integrated into a modern command network must meet rigorous accreditation processes, such as the Army’s “Authority to Operate” framework. These reviews ensure that the system can be deployed without compromising security or reliability.

In the NGC2 case, the Army’s chief technology officer noted that third-party applications embedded within the system contained hundreds of vulnerabilities that had not yet undergone formal assessment. One application alone reportedly held 25 high-severity code flaws. Such lapses are not mere bureaucratic oversights, they reflect the gap between rapid innovation and secure implementation.

Behind the digital firewalls and AI algorithms, there’s a human dimension to this story. Every glitch in a command system has a downstream effect on soldiers relying on coordinates, pilots waiting for real-time data, or commanders making split-second decisions. The integrity of battlefield networks is not an abstract cybersecurity concern; it’s a matter of operational survival. When networks fail, units can lose synchronization, missions can be compromised, and soldiers can be exposed to unnecessary risk. In this sense, cybersecurity is not a technical discipline, it’s force protection.

If defense innovation is to maintain both its speed and its credibility, the next phase of modernization must be built on a new doctrine: secure by design. Cybersecurity cannot be a final checkbox before deployment – it must be embedded from the first line of code to the final field test. It also requires a shift in culture. The defense establishment must continue to embrace nontraditional vendors, but it must do so with clear expectations and uncompromising standards. Innovation must never outpace oversight.

Programs like continuous Authority to Operate (cATO), which allow for ongoing, real-time security updates rather than slow certification cycles, are a step in the right direction. They align the need for agility with the need for assurance.

The Anduril–Palantir case is not a failure of technology; it’s a stress test for the future of defense innovation. It raises a fundamental question: in the race to digitize the battlefield, are we moving faster than we can secure? The answer will define the next decade of military procurement. Because in the end, readiness isn’t measured by how quickly a prototype rolls out. It’s measured by whether it can be trusted when it matters most. Innovation wins wars only when it protects the people fighting them.

Leave a comment